Google the training routine of any professional athlete and you will be surprised at the sheer numbers of staff in the coaching team and the complexity of their training regimen. The coaching entourage often includes at minimum, a physiotherapist, nutritionist, psychology, data/video analyst, fitness coach and a team of coaches dedicated to every technical aspect of the sport. (Attacking, defending, stroke, dribbling, tackling, serve…. etc)

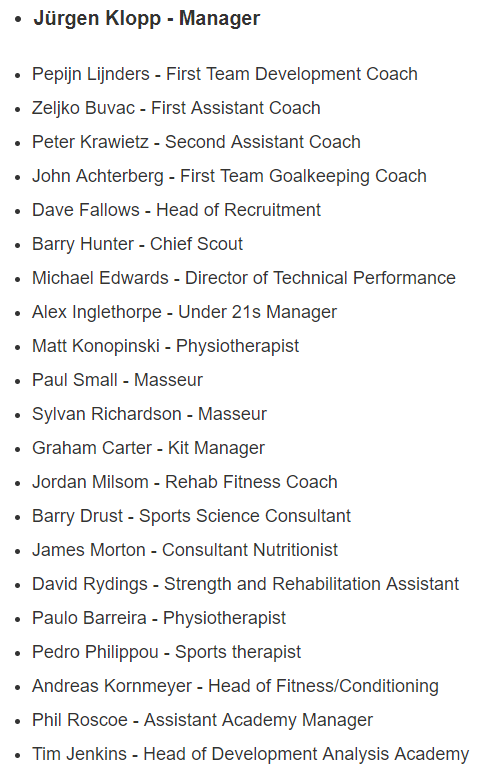

Liverpool Football Club Coaching Team:

Most competitive sports are games of small margins, where competitors spend hours each day trying to optimize every aspect of their playing skill, their psychology and their physical conditioning in order to create a wafer-thin edge over the rest. After all, the tiniest of advantages can mean the difference between becoming the best, claiming fame glory and riches as compared to being above average and forgettable.

If you ask most debaters what their training routine looks like however, and most will give you the same answer: prep, debate, debrief, rinse and repeat. If any athlete in any other competitive sport were to claim that their training routine consisted mainly of “just playing as many matches as possible”, they would be laughed at, yet that’s exactly what most competitive debaters do on a regular basis.

Getting match practice and feedback is of course an integral part of any training regimen for any athlete, but it is almost always the least time-consuming part of their routine. For every hour spent actually competing in the sport, many more are spent analyzing videos, working on a variety of drills and optimizing fitness levels and mental state. Some of these drills and practices may seem absolutely bizarre, where it may almost be difficult for an outsider to imagine why they may be relevant. Such as Stephen Curry, the Most Valuable Player of the NBA juggling tennis balls.

Most debate societies don’t do much else beyond debating rounds over and over again and that seems to me like an awfully sub-optimal way of training for a number of reasons:

1) Unless you have access to a top notch coach or adjudicator, you won’t even gain access to any valuable feedback or evaluation. If club members are rotated as adjudicators, you may end up having a case of the blind leading the blind.

2) An inexperienced adjudicator may even end up making the wrong call for completely arbitrary reasons or worse still provide faulty advice and feedback that may damage a debater’s ability to improve by encouraging bad habits.

3) Habits are hard to break. In high pressure situations, like debate tournaments, we are likely to experience what psychologists would call a flight or fight reaction. Put simply, we experience stress-related discomfort, and a burning need to make ourselves feel comfortable.

In those situations, our instincts take over, and we revert to tried-and-tested methods and habits that have been internalized and reinforced over time. Just as a Tennis player doesn’t have to actively think and scrutinize each stroke they make, debaters generally do not have the time to figure out what to say in the heat of the moment, especially in short-preparation, impromptu rounds.

4) In those situations, if we have developed a series of bad habits over time that have been reinforced during repeated training sessions, our training methods may actually hurt us. To draw an analogy, racket sports players often suffer from joint and muscular injuries because of an inefficient stroke and form. Similarly NBA players who jump multiple times in a match without learning proper landing technique can end up with career-threatening injuries due to repeated stress on their joints.

In these circumstances, poor technique practiced over and over again will actually hurt, rather than help us.

5) Even in the best case scenario, where a skilled coach or adjudicator is able to highlight what your strengths and weaknesses are, they usually will not be able to help you rectify your problems.

For example, an experienced adjudicator may be able to point out that you have to work on your rebuttals. They may highlight why your rebuttals in a given debate are weak and offer suggestions on what you could have argued instead, they may even recommend some debate videos of world-class debaters whom you may try to emulate, but there is nothing the judge can do in the short term to actually improve your ability to engage.

Let’s use another sports analogy to illustrate this: no matter how many times I watch Stephen Curry shoot a three-pointer or Cristiano Ronaldo take a freekick, I am not going to magically be able to absorb their sporting prowess. Even if I know exactly why my shooting form is bad, looking at someone else do it better isn’t going to actually help me improve, neither is it going to let me know what I have to do in order to improve. What I would need in this situation would be to engage in shooting practice over and over again, work on every minor detail, hopefully in the presence of a skilled trainer to provide specific guidance.

In reality, such coaching resources are expensive and beyond the reach and budget of most people. Even if your debate club or society has the budget to hire a coach for hundreds or thousands a month, there are many practical problems which mean you are unlikely to get such intensive, personal attention.

There are a number of reasons for this:

1) The expectations of students

Most people join a debate society so that they can have an opportunity to debate. Debating can be fun and addictive and that is part of the reason why many people invest so much of their time and money into the activity. Being in a debate can bring a feeling of excitement and exhilaration that can be immensely enjoyable, and most debaters look forward to training so that they can spar each other.

As a result, most debate societies and coaches have to give in to their students and members and have practice debates in order to keep them happy. If debaters were told that training sessions would involve watching a video of a debate speech, writing out rebuttals and submitting their answers as homework to be marked by the coach followed by a few hours of listening to the coach go through their answers, many debaters would have their enthusiasm for the activity dampened.

2) Large club sizes

Debate clubs are funded by schools and universities. This usually means that there is a need to recruit sufficient members to convince the school to fund them. Since debate is a team sport, this also means that a debate club will need to have at least 6-8 members in each cohort to be sustainable. Furthermore, the presence of debaters of different age and skill levels who specialize in different positions can make it difficult if not impossible to devise a one-size fits all training plan that will be valuable to everyone while keeping them interested and engaged.

3) Time constraints

Debating is time consuming. Between the 15-60min preparation time, 1 hour long debate, 15 minutes for the judge to deliberate and 30 minutes for the verdict and feedback, each debate can last 2-3 hours. Unlike most other team sports, where multiple players are on the pitch at the same time, only one person can speak on the floor at any point in time. This means that in the span of a few hours, each debater only gets to speak for 6-8 minutes.

The additional challenge of debate coaching is that each student requires personalized attention simply to track everything that is being said, and the feedback for each student often may not be as useful to every other student. All the above factors mean that coaches who are usually only able to conduct sessions once or twice a week often have to structure trainings around prep, debate, debrief just so that students get enough match practice and feedback to work on.

4) Not knowing better

The majority of debate coaches were previously part of debate clubs where all they did was engage exclusively in practice debates. As a result, such training methods remain primitive as they are passed down from generation to generation. There is also little incentive for coaches to innovate their training methods because the demand for qualified and experienced trainers far exceeds the supply. Moreover, most debate coaches were trained by previous generation of coaches who usually also subjected them to the formula of prep, debate, debrief, rinse and repeat.

When I was entering into my 3rd year of varsity debating, my debate club entered into a crisis. All my seniors had graduated and all my juniors had quit, leaving the club with just two members, me and my regular BP partner. I did not know it then, but the situation turned out to be a blessing in disguise, as the following months of training were the most intensive and productive sessions I have ever experienced, and both of us went through unprecedented growth spurts in our debate careers. In fact, when the new academic year began and we recruited a new batch of freshmen, we missed training on our own so much that we continued having additional training sessions on our own.

Training Method 1: 1 On 1 sparring

It was during those few months where we were short on members that we had to experiment with different training methods, many of which I have continued to employ for myself and my students over the years. In our first session, we did a series of Prime Minister (1st Proposition) vs Leader of Opposition (1st Opposition) speeches, which as you would quickly realize was no different from the prep, debate, debrief formula. The difference was, a single PM vs LO practice along with critiquing each other’s speeches took up less than an hour, and within a normal 3 hour session we could finish 3 debate rounds, which would be the equivalent of one day’s work at a debate tournament.

Initially, we worried that this would be a poor substitute for participating in full debates, but we quickly realized that we were instead experiencing a spike in our performances. Basically, we had stumbled upon the hyperbolic time chamber in Dragonball. Instead of spending 3 hours on a debate where we would normally speak for only 7 minutes and spend the rest of the time brainstorming Points of Information, we ended up having multiple hour long debates where we had to prep alone, spar each other and then find fault with each other’s speeches. Needless to say, these sessions were intense, extremely stressful and engaging, but they also turned out to be a brilliant way to train.

Here are 3 reasons why:

1. Focused Training

Having full debates, like playing friendly matches for sports, definitely helps to get in shape for actual competitions by providing a useful simulation. 1 on 1 practice, on the other hand, are much more efficient for working on a specific skillset, such as improving your ability to prep and case-set.

2. Repetition creates a positive feedback loop

Feedback and lessons learnt from the first short drill can be immediately applied on the next practice immediately after, such that you can evaluate whether the changes you would like to make to your speeches are effectively applied. This is far more effective than waiting a few days for the next training session where your memory of the previous session has become hazy.

3. Staying engaged

After each PM vs LO exchange, we reviewed a video recording of our speeches and gave each other extensive feedback on what we liked and what we wished to improve upon. This ensured that we were constantly engaged and challenged throughout the entire training session, where we had to prep alone without relying on teammates, critically evaluate each other’s performances before having a very intense discussion over the arguments and issues within the debate. This kept us constantly engaged throughout and made our training session more efficient in comparison to a full debate practice where we could afford to zone out after our speeches and when the judge is giving feedback to other speakers.

Training Method 2: Inserting yourself into a video

After a few weeks of doing one-on-one practice, we saw marked improvement in our prep efficiency, case-setting and elaboration of our arguments, there was just a tiny problem: since there were only two of us, we could not get any practice in any other position except 1st speaker. We wanted to get practice doing Closing, but struggled to get anyone else to show up for training. Eventually, we settled on inserting ourselves into a debate based on the video we watched.

So what we would do was to prep a debate based on the motion of a video with world class debaters. We would prep for 15 minutes pretending we were CG and CO members and then watched the Opening half of the debate video before giving the Gov Member and Opp Member speeches respectively. We would then watch the actual member speeches in the debate video to compare our speeches against the world class debaters in that video.

We quickly realized that inserting ourselves into a debate video was actually very effective as a training method because it gave us not only the opportunity to test ourselves against world class debaters overseas but also the ability to compare our speeches with those debaters, all without spending a single cent. A large part of judging and coaching involves telling the debaters what they could have done better and debate videos of top-notch debaters is a great substitute for an actual world-class coach or judge.

Training Method 3: Debate every position

This is a combination of Training Method 1 and 2.

First of all, my teammate and I would pick a side each for a debate, let’s assume I end up being on the Government side. I would prep and then deliver a PM (1st Prop) speech, we would watch the actual PM speech of a debate video and compare what I did well or badly, after which my teammate would do a LO (1st Opp) speech responding to the PM speech given in the debate video. We would then watch the LO speech to compare before I would give a DPM (2nd Prop) speech responding to the LO speech in the debate video.

It sounds like we would end up feeling a little schizophrenic and pathetic but once we got used to the exercise it was... almost bearable. Having to iron-man 4 speeches on each side while responding to 4 world-class debaters was way intense and exhausting, but it forced us to get comfortable with being put in high-pressure situations, getting creative with our argumentation and developing stamina for Major competitions where we would have to debate more than 10 rounds. We would later use this exercise specifically for motions and themes which we were least comfortable with, as there was no better way to master how to debate a certain type of motion than to ironman an entire Government and Opposition bench.

If all this sounds like absolute madness, that’s because it is absolute madness. I would highly recommend starting with doing only Opening House first.

There were many other training methods that I would love to share with you but our chief editor Reuben Lopez would probably shout at me for exceeding his recommended word count, so I will probably elaborate further in a future article. For now though, we will have to make do with sharing this image.